COOL WORLD Storyboards by Louise Zingarelli

5 de noviembre de 2019

5 de noviembre de 2019

color notation

https://color.adobe.com/create

From the Munsell Book: (color theory)

from http://www.handprint.com/HP/WCL/color14.html (color mixing)

5 de noviembre de 2019

3 de noviembre de 2019

split primary palette

The Dogma. If the artist limits his paint selection to the traditional primary triad palette, then the saturation costs in secondary color mixtures (orange, purple and green) are so severe that even some artists committed to their primary color dogma look for a way to reduce them.

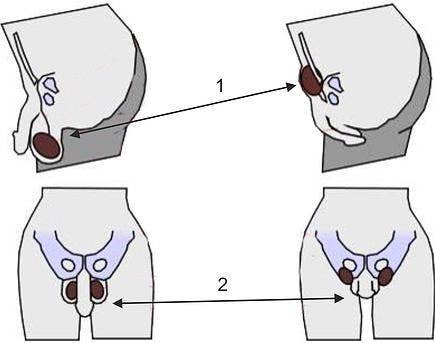

The common remedy has been to split each "primary" color into a pair of colors, each leaning toward one of the other two "primaries." So the single primary yellow paint is replaced by two paints: a warm (deep) yellow that "leans toward" (is tinted by) the red "primary," and a cool (light) yellow that leans toward blue. Similar replacements are made for the other two "primaries," which doubles the palette from three to six paints.

the split primary palette

the version proposed by Nita Leland

According to Nita Leland, a representative split primary palette would consist of:

• warm blue : ultramarine blue (PB29) (leans toward red)

• cool blue : phthalocyanine blue GS (PB15:3) (leans toward yellow)

The color theory logic for these substitutions goes like this: a yellow that leans toward blue is a yellow that actually contains blue, and a blue that leans towards yellow is a blue that contains yellow. So the blue and yellow reinforce each other when mixed to make green. But if either color leans toward red, then red is carried into the mixture through the yellow or blue paints. This isn't good, because mixing all three primaries creates gray or black, and this dulls the remaining green mixture.

This becomes a rule: when mixing two primary colors, choose the paints that lean toward each other to get the most vibrant mixture. The slogan is, "never put the mixing line across a 'primary' color" — that is, don't choose either two primaries leaning toward or tinted with the third primary, because mixtures containing all three primaries mix to gray. Split primary advocates call these mixtures "mud."

Of course, the painter can intentionally choose one or both of the primaries leaning toward the third primary, if he wants less intense or near neutral mixtures. But then color theory painters will call his paintings mud.

The Critique. Where did these muddled recommendations come from? Straight out of the Newtonian color confusions of the 18th century. Essentially the same color concepts appear in the color wheel text by Moses Harris, and are accepted without serious challenge in Michel-Eugène Chevreul's The Principles of Color Harmony and Contrast (1839). Chevreul describes color mixing beliefs that must have been widely accepted by artists of his time; one passage is worth quoting at length:

We know of no substance [pigment or dye] that represents a primary color — that is, that reflects only one kind of colored light, whether pure red, blue or yellow. ... As pure colored materials do not exist, how can one say that violet, green and orange are composed of two simple colors mixed in equal proportions? ... Instead we discover that most of the red, blue or yellow colored substances we know of, when mixed with each other, produce violets, greens and oranges of an inferior intensity and clarity to those pure violet, green or orange colored materials found in nature. They [the authors of color mixing systems] could explain this if they admitted that the colored materials mixed together reflect at least two kinds of colored light [that is, two of the three primary colors], and if they agreed with painters and dyers that a mixture of materials which separately reflect red, yellow and blue will produce some quantity of black, which dulls the intensity of the mixture. It is also certain that the violets, greens and oranges resulting from a mixture of colored materials are much more intense when the colors of these materials are more similar in hue. For example: when we mix blue and red to form violet, the result will be better if we take a red tinted with blue, and a blue tinted with red, rather than a red or blue leaning toward yellow; in the same way, a blue tinted with green, mixed with a yellow tinted with blue, will yield a purer green than if red were part of either color. [1839, ¶¶157-158; my translation]

There you have the color ideas behind the split primary palette. Unfortunately, most of them are factually wrong or logically unrelated.

Chevreul is criticizing the idea that "primary" colors can be represented in paints by observing that these primary paints can't mix all the hues of nature with sufficient intensity or chroma. From that he concludes that paint pigments do not reflect "only one kind of light". A yellow primary paint must reflect "yellow" light mixed with some "blue" or "red" light, which dulls the pure yellow color. As we can't avoid this color pollution, we minimize it by mixing colors tinted with each other — so the thinking goes.

However, paint colors do not simply represent spectral "colors" as Chevreul believed: a primary yellow paint does not just reflect a lot of "yellow" light. Nor is color "in the light" as colored light; there are no "magenta," "red violet" or "purple" wavelengths in the spectrum, so those colors cannot be "in" the light. The same surface colors can result from very different light mixtures: yellow results from a "red" and "green" mixture, and red violet from a "blue violet" and "red" mixture. These confusions were clarified later in the 19th century through the popularizing science books by Hermann von Helmholtz and Ogden Rood. Surprising, then, that the "paint color equals light color" fallacy is still widely believed by painters today — Michael Wilcox teaches it as the basis of his color mixing system.

In addition, you can never find a paint, a crystal — or a light — whose color is "pure enough" to match a primary color. This is because primary colors are always imaginary or imperfect: they can never be matched by visible lights or paints, and visible lights or paints can never mix all possible colors. The reason for this lies in the design of our eye — in the overlapping response curves of the L, M and S light receptors. The "impurity" of the light reflected by the paint certainly aggravates the problem, but is not the cause of it. The "color theorist" dogma that paint mixing problems arise because paints are "impure colors" is bogus.

Choosing two paints or inks that are more similar in hue does increase the intensity of their mixture, as Chevreul says. But these saturation costs again have nothing to do with the contamination of one primary color with another. They appear even when we mix monochromatic (single wavelength) lights that are completely free of tint by any other hue. In fact, mixing pure spectral lights was how Newton discovered saturation costs in the first place!

In brief, the split primary palette is based on 19th century color ideas that have nothing to do with the facts of color perception and color mixing as we understand them today.

The Demonstration. But the pragmatist may say: who cares? Just because the justification is murky doesn't mean that the split primary palette isn't an effective selection of paints.

Fair enough. So let's hold the split primary palette to its two key claims: (1) that red and blue (rather than magenta and cyan) are the most effective primary colors; and (2) that splitting these primary colors allows us to mix the most vibrant secondary colors (orange, purple and green). It's easy to show that both these claims are false.

A "pure" red or blue makes an ineffective primary color because these colors fail the basic requirement for a subtractive primary paint: it must strongly stimulate two receptor cones but not the third. A pure red and pure blue paint mix dark, grayed purples, for example, because they have almost no reflectance in common; for the same reason, the blue and yellow make very dull greens. So the split primary palette starts out with an inaccurate definition of the primary paints most useful for subtractive color mixtures.

We can evaluate the second, "vibrant color" justification for the split primary palette by comparing it to any other palette of six paints, for example the secondary palette, to see which paint selection is superior. There are two ways to do this.

A simple "back of the envelope" approach is to print out a copy of the pigment map presented on the CIECAM aCbC plane, identify on this map the location of the pigments used in all paints in the palette (use the complete palette to identify specific pigments), then connect these pigment markers to form the largest possible, straight sided enclosure (see examples below). The closed area is the gamut of the palette — the approximate range of hue and saturation that it is possible to mix with that selection of paints. The palette with the larger gamut will create a wider range of color mixtures.

comparing the gamut of two palettes

split primary palette (left) and secondary palette (right)

on CIECAM aCbC plane

on CIECAM aCbC plane

The split primary palette (at left) creates a narrow lozenge of color mixtures that is skewed toward the "warm" colors of the palette, and puts the heaviest saturation costs (dull mixtures) in the mixed greens and violets. In contrast, with the equally spaced secondary palette (at right), we get a substantially increased range in color mixtures. This is because a single intense pigment anchors each primary and secondary hue, which pushes back the limits of the color space as far as possible (particularly on the green side). Same number of paints, very different gamuts.

The alternative (and better) way to compare palettes is to use each one to mix the twelve colors of a tertiary color wheel. Display these mixtures either side by side or as matching paint wheels (below), and see what you get.

comparing paint wheels made with two palettes

split primary palette (left) and secondary palette (right)

This side by side comparison confirms the gamut differences identified with the palette schemes. The mixed red orange in the split primary palette (left) is so dull it is close to brown; the purple is dark and grayish, and the mixed greens are drab across the entire range. In contrast, the secondary palette (at right) is obviously much brighter in the greens, produces a more evenly saturated range of warm hues, and gets juicy purples as well. If you don't want "mud," then the split primary palette is not the one to choose!

Can we fix these problems by changing the selection of split primary paints? Yes we can, and the solutions people choose are revealing. The palette scheme for the Wilcox six principle [he means principal] colors shows that his split primaries have turned into the secondary color wheel, but with green omitted in order to provide two very similar yellows.

palette scheme for the Wilcox six principal colors

from "Blue and Yellow Don't Make Green" (2001)

Wilcox has widened the split between the red and blue primaries to the point where they are completely different hues (scarlet and magenta, or blue violet and green blue) — yet he still hangs onto his two similar "primary" yellows. This is a funny and revealing example of how a color dogma accepted without question (you must use primary colors!) can trample on color mixing common sense (hey, mixtures look so much brighter if you add a scarlet, blue violet and green paint!).

Not only have we found that the split primary palette fails to meet its claims, and its color theory justifications are inaccurate, I've proven by demonstration and explanation that the secondary palette is the superior mixing system. And because it lets the painter choose many different paints for the three contrasting pairs of complementary pigments, the secondary palette offers the largest gamut and value range, and the greatest alternative choices of transparency, staining, granulation, texture, and handling attributes in paints that are possible with a six paint palette. Try it for yourself and see.

unequal color spacing

Increasing the color wheel or hue circle distance between two paints increases the saturation cost or dullness in their midpoint mixtures, and within the "primary" triad or split "primary" frameworks this effect is most pronounced in orange, purple and green colors. By manipulating the bright or dull mixing potential of these purples and greens, the artist can shape the fundamental color dynamics of his painting palette.

unequally spaced colors and the implied illuminant

The color wheel schematic (above) shows the two main variations painters are likely to use: when the illuminant — the color of light — shifts warmer (toward longer wavelengths, becoming yellowish or reddish) or greener (the color of intense noon sunlight).

The basic principle is that when the illuminant has a distinct color, it brightens similar hues and dulls complementary hues.

Warmer Color Shifts. In this case, typical of late afternoon light or artificial light from a candle or incandescent light, warm colors become more saturated and cool colors become darker and duller.

This suggests choosing warm color (red to yellow) paints that have higher saturation and cool color (blue) paints that are relatively darker and duller. Burnt sienna would be replaced by cadmium orange, and phthalocyanine blue by iron [prussian] blue or a red shade of phthalo blue.

Provided the light yellow is not too pale (greenish), all mixed yellows will be very saturated and light valued. If the "cool" red is shifted from a bright quinacridone magenta to quinacridone red, and the "warm" red into red orange, the saturation of mixed warm hues will be consistently at maximum saturation.

The greens mixed from yellow and blue will be moderately dull and somewhat dark. These muted greens yield dominance to the more intense reds and oranges, reducing the fundamental visual tension between red and green. Because all the greens must be mixed, they will be more varied and interesting.

The blue paints are typically grouped close together, so the mixed middle blues will be relatively bright, but quickly become muted as they are mixed with the "cool" yellow or red. This gives the range of blues a chromatic emphasis around the sky color, surrounded by a range of less intense green blue and blue violet mixtures for foliage and shadows. The mixed violets will be somewhat dull, and dull dark blues (the visual complements of yellow or red orange), not purples, should be used to tint shadows.

Greener Color Shifts. A "green" color shift is characteristic of colors under intense noon sunlight. Daylight does not appear green to our eyes because of the color balancing effect of chromatic adaptation, but the relative color emphasis that results can be modeled by different palette choices.

The main effect of this greening is to brighten greens and to dull purples (because purples are the complementary hue of the light). As there are few useful purple or green pigments, the most common method to produce this bias is to shift the yellow and blue paints toward each other — by choosing a lemon or greenish yellow as the "cool" yellow, and a greenish or turquoise blue for the "cool" blue — thereby increasing the saturation of green mixtures. The greenish blue should also be somewhat lighter valued, if possible: cobalt turquoise or cobalt teal blue (PG50) are very useful alternatives.

In contrast, the hue circle distance between the "cool" red and "warm" blue should be increased, and one of the colors should be dark valued, if feasible — for example, by choosing a phthalo blue red shade or a quinacridone carmine. These will produce dull dark purples that are usefil to tint shadows with the complementary hue of the illuminant color.

Other imbalanced distributions are possible, which might contrast a broad range of blues against dull earths, vibrant greens against dull reds, and so on in many combinations. But the palette shown in the figure, with most of the saturation costs in the violets and greens, is one of the most popular; dozens of palettes are variations on it.

Why not just choose a large number of paints that are very closely spaced all the way around the color wheel? You can, if you want. These colorist palettes are useful for a bright and lively style of painting that specifically does not give the impression of a certain kind of light. The point is that saturation costs can buy you expressive resources, particularly in landscapes and portraits. Forcing some color mixtures to be dull confers a light giving power to the pure colors they are mixed from, which can create a deep color harmony across the value structure of a painting.

16 de octubre de 2019

[Explanation: I have put this piece of writing together to look into the relationships between the visual and sound/music. It contains mostly Wikipedia articles intersected by a few personal notes. It is long but wanted to make sure I kept a record of an idea that has been circling my mind. That is, my work and how it operates in relation to music. Why there are figures dancing? Why do I choose certain colors? How do I include the time dimension in my work? Do for me images generate sound? or does sound trigger imagery? What would the reversal of this process look like? Would it be in the form a sound-sculpture? Who is the performer in these drawings? How is movement annotated? Can a score be spatialised? etc.

This is something I am still -and probably always will be- trying to understand. This is for now a quick research sketch]

The Definition of Synesthesia

Synesthesia is a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. People who report a lifelong history of such experiences are known as synesthetes. Awareness of synesthetic perceptions varies from person to person.

In one common form of synesthesia, known as grapheme-color synesthesia or color-graphemic synesthesia, letters or numbers are perceived as inherently colored. In spatial-sequence, or number form synesthesia, numbers, months of the year, or days of the week elicit precise locations in space (for example, 1980 may be "farther away" than 1990), or may appear as a three-dimensional map (clockwise or counterclockwise). Synesthetic associations can occur in any combination and any number of senses or cognitive pathways.

Little is known about how synesthesia develops. It has been suggested that synesthesia develops during childhood when children are intensively engaged with abstract concepts for the first time. This hypothesis – referred to as semantic vacuum hypothesis – explains why the most common forms of synesthesia are grapheme-color, spatial sequence and number form. These are usually the first abstract concepts that educational systems require children to learn. Difficulties have been recognized in adequately defining synesthesia. Many different phenomena have been included in the term synesthesia ("union of the senses"), and in many cases the terminology seems to be inaccurate. A more accurate but less common term may be ideasthesia.

The earliest recorded case of synesthesia is attributed to the Oxford University academic and philosopher John Locke, who, in 1690, made a report about a blind man who said he experienced the color scarlet when he heard the sound of a trumpet. However, there is disagreement as to whether Locke described an actual instance of synesthesia or was using a metaphor. The first medical account came from German physician, Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs in 1812. The term is from the Ancient Greek σύν syn, "together", and αἴσθησις aisthēsis, "sensation".

Types of Synesthesia

There are two overall forms of synesthesia:

-projective synesthesia: people who see actual colors, forms, or shapes when stimulated (the widely understood version of synesthesia).

-associative synesthesia: people who feel a very strong and involuntary connection between the stimulus and the sense that it triggers. For example, in chromesthesia (sound to color), a projector may hear a trumpet, and see an orange triangle in space, while an associator might hear a trumpet, and think very strongly that it sounds "orange".

Synesthesia can occur between nearly any two senses or perceptual modes, and at least one synesthete, Solomon Shereshevsky, experienced synesthesia that linked all five senses. Types of synesthesia are indicated by using the notation x → y, where x is the "inducer" or trigger experience, and y is the "concurrent" or additional experience. For example, perceiving letters and numbers (collectively called graphemes) as colored would be indicated as grapheme → color synesthesia.

Similarly, when synesthetes see colors and movement as a result of hearing musical tones, it would be indicated as tone → (color, movement) synesthesia. While nearly every logically possible

combination of experiences can occur, several types are more common than others.

On a personal note: This is most closely describing my case: seeing landscapes, forms, sculptures, movement, colors, fashions, as a result of hearing music. Music triggers these visual images in my head. These I always try to translate into my drawings.

The colors triggered by certain sounds, and any other synesthetic visual experiences, are referred to as photisms.

According to Richard Cytowic, chromesthesia is "something like fireworks": voice, music, and assorted environmental sounds such as clattering dishes or dog barks trigger color and firework shapes that arise, move around, and then fade when the sound ends. Sound often changes the perceived hue, brightness, scintillation, and directional movement.

Some individuals see music on a "screen" in front of their faces. For Deni Simon, music produces waving lines "like oscilloscope configurations – lines moving in color, often metallic with height, width and, most importantly, depth. My favorite music has lines that extend horizontally beyond the 'screen' area."

Individuals rarely agree on what color a given sound is. B flat might be orange for one person and blue for another. Composers Franz Liszt and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov famously disagreed on the colors of music keys.

Signs and symptoms

The automatic and ineffable nature of a synesthetic experience means that the pairing may not seem out of the ordinary. This involuntary and consistent nature helps define synesthesia as a real experience. Most synesthetes report that their experiences are pleasant or neutral, although, in rare cases, synesthetes report that their experiences can lead to a degree of sensory overload.

Synesthetes are very likely to participate in creative activities. It has been suggested that individual development of perceptual and cognitive skills, in addition to one's cultural environment, produces the variety in awareness and practical use of synesthetic phenomena. Synesthesia may also give a memory advantage. In one study conducted by Julia Simner of the University of Edinburgh it was found that spatial sequence synesthetes have a built-in and automatic mnemonic reference. So the non-synesthete will need to create a mnemonic device to remember a sequence (like dates in a diary), but the synesthete can simply reference their spatial visualizations.

Neurologist Richard Cytowic identifies the following diagnostic criteria for synesthesia in his first edition book. However, the criteria are different in the second book:

-Synesthesia is involuntary and automatic.

-Synesthetic perceptions are spatially extended, meaning they often have a sense of "location." For example, synesthetes speak of "looking at" or "going to" a particular place to attend to the experience.

-Synesthetic percepts are consistent and generic (i.e. simple rather than pictorial).

-Synesthesia is highly memorable.

Synesthesia is laden with affect.

There is research to suggest that the likelihood of having synesthesia is greater in people with autism.

Researchers hope that the study of synesthesia will provide better understanding of consciousness and its neural correlates. In particular, synesthesia might be relevant to the philosophical problem of qualia, given that synesthetes experience extra qualia (e.g. colored sound). An important insight for qualia research may come from the findings that synesthesia has the properties of ideasthesia, which then suggest a crucial role of conceptualization processes in generating qualia.

Notable cases

One of the most notable synesthetes is Solomon Shereshevsky, a newspaper reporter turned celebrated mnemonist, who was discovered by Russian neuropsychologist, Alexander Luria, to have a rare fivefold form of synesthesia. Words and text were not only associated with highly vivid visuo-spatial imagery but also sound, taste, color, and sensation. Shereshevsky could recount endless details of many things without form, from lists of names to decades-old conversations, but he had great difficulty grasping abstract concepts. The automatic, and nearly permanent, retention of every little detail due to synesthesia greatly inhibited Shereshevsky from understanding much of what he read or heard.

*******************************************

Visual music

Visual music, sometimes called colour music, refers to the use of musical structures in visual imagery, which can also include silent films or silent Lumia work. It also refers to methods or devices which can translate sounds or music into a related visual presentation.

An expanded definition may include the translation of music to painting; this was the original definition of the term, as coined by Roger Fry in 1912 to describe the work of Wassily Kandinsky.

There are a variety of definitions of visual music, particularly as the field continues to expand.

In some recent writing, usually in the fine art world, visual music is often confused with or defined as synaesthesia, though historically this has never been a definition of visual music. Visual music has also been defined as a form of intermedia. Visual music also refers to systems which convert music or sound directly into visual forms, such as film, video, computer graphics, installations or performances by means of a mechanical instrument, an artist's interpretation (dance, performance, movement), or a computer.

Famous visual music artists include Jordan Belson, Oskar Fischinger, Norman McLaren, John Whitney Sr., and Thomas Wilfred, plus a number contemporary artists.

Visual Music On film

Visual music and abstract film or video often coincide. Some of the earliest known films of these two genres were hand-painted works produced by the Futurists Bruno Corra and Arnaldo Ginna between 1911 and 1912 (as they report in the Futurist Manifesto of Cinema), which are now lost.

Mary Hallock-Greenewalt produced several reels of hand-painted films (although not traditional motion pictures) that are held by the Historical Society of Philadelphia. Like the Futurist films, and many other visual music films, her 'films' were meant to be a visualization of musical form.

Notable visual music filmmakers include: Walter Ruttmann, Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling, Oskar Fischinger, Len Lye, Jordan Belson, Norman McLaren, Harry Smith, Hy Hirsh, John and James Whitney, Steven Woloshen and many others up to present day. Artist Larry Cuba, founded the iota Fund in 1994, which was later called iotaCenter. They currently own the films of such artists as Sara Petty, Adam Beckett, some of the films of Jules Engel, Sky David, Robert Darroll and others. They hosted the renowned Kinetica programs (1999–2003) touring the world introducing new audiences to the wonders of visual music.

Computer Graphics

The cathode ray tube made possible the oscilloscope, an early electronic device that can produce images that are easily associated with sounds from microphones. The modern Laser lighting display displays wave patterns produced by similar circuitry.

The imagery used to represent audio in digital audio workstations is largely based on familiar oscilloscope patterns. The Animusic company (originally called 'Visual Music') has repeatedly demonstrated the use of computers to convert music — principally pop-rock based and composed as MIDI events — to animations.

Graphic artist-designed virtual instruments which either play themselves or are played by virtual objects are all, along with the sounds, controlled by MIDI instructions. In the image-to-sound sphere, MetaSynth includes a feature which converts images to sounds. A reverse function allows the creation of images from sounds.

Some media player software generates animated imagery or music visualization based on a piece of recorded music: autom@ted_VisualMusiC_ 4.0 planned and realized by Sergio Maltagliati. This program can be configured to create random multiple visual-music variations, starting from a simple sonorous/visual cell. It generates a new and original audio-visual composition each time play is clicked.

Graphic notation

On a personal note: this is very important to me. I have always thought of the drawings I make as being strongly related to the music I listen to. The drawings I make are mostly related to the sounds I hear, and some personal experiences/emotions. Notation bridges this space of correlation between sound/movement/color, spatial location and shape. Its an illustration of these relationships that can also be actioned, reproduced and interpreted by other agents.

In a way they are visual notations of music. They are not drawings which would allow agents to recompose music, or perform music. But rather they are codified performances to a set of sounds. Provided that the same soundsystem/composition is available, they would allow others to recreate a particular performance actioned after a certain set of sounds.

This means that the drawings are equivalents to more traditional forms of fashion, set, sculpture and painting design. Scores and dance notation come into play because they add the time element/dimension to the otherwise more "static" elements of sculpture, painting, set design, architecture/urbanisms, that advance a more synesthetic type of performance, in which form, color, and movement, can be notated in a sequence embedded in a progression of time.

The picture below (pic.1) shows a very early, very rudimentary attempt of mine, at finding a way of notating the form, color and style in a progression that considers movement in response to a very specific type of sound. In this case notated in the traditional form of a stave. This would fall inside the sound to image phenomenon.

The obvious progression to this, is making the setting playable. The idea that the installation, the sculptures and the environment can be notated to produce sound in itself. This is almost the reverse as a case of image to sound phenomenon. Making the setting/sculpture a "musical" instrument. I will continue this topic this later in the text.

pic.1 synesthetic notation #1 - All rights reserved

Many composers have applied graphic notation to write compositions. Pioneering examples are the graphical scores of John Cage and Morton Feldman. Also known is the graphical score of György Ligetis Artikulation designed by Rainer Wehinger. Musical theorists such as Harry Partch, Erv Wilson, Ivor Darreg, Glenn Branca, and Yuri Landman applied geometry in detailed visual musical diagrams explaining microtonal structures and musical scales.

Cymatics

This also plays a role in the sound to image phenomenon but I will not go into it here as I find it too restrictive, and has a very short interpretative span. The step is too tight/close to sound.

VJing

It is a broad designation for realtime visual performance. Characteristics of VJing are the creation or manipulation of imagery in realtime through technological mediation and for an audience, in synchronization to music.

VJing often takes place at events such as concerts, nightclubs, music festivals and sometimes in combination with other performative arts. This results in a live multimedia performance that can include music, actors and dancers. The term VJing became popular in its association with MTV's Video Jockey but its origins date back to the New York club scene of the 70s. In both situations VJing is the manipulation or selection of visuals, the same way DJing is a selection and manipulation of audio. One of the key elements in the practice of VJing is the realtime mix of content from a "library of media", on storage media such as VHS tapes or DVDs, video and still image files on computer hard drives, live camera input, or from computer generated visuals.

In addition to the selection of media, VJing mostly implies realtime processing of the visual material. The term is also used to describe the performative use of generative software, although the word "becomes dubious (...) since no video is being mixed".

Antecedents

The Exploding Plastic Inevitable, between 1966 and 1967, organized by Andy Warhol contributed to the fusion of music and visuals in a party context. "The Exploding Party project examined the history of the party as an experimental artistic format, focusing in particular on music visualization - also in live contexts".

Groups like Cabaret Voltaire started to use low cost video editing equipment to create their own time-based collages for their sound works. In their words, "before [the use of video], you had to do collages on paper, but now you present them in rhythm—living time—in video." The film collages made by and for groups such as the Test Dept, Throbbing Gristle and San Francisco's Tuxedomoon became part of their live shows.

An example of mixing film with live performance is that of Public Image Ltd. at the Ritz Riot in 1981. This club, located on the East 9th St in New York, had a state of the art video projection system. It was used to show a combination of prerecorded and live video on the club's screen. PiL played behind this screen with lights rear projecting their shadows on to the screen. Expecting a more traditional rock show, the audience reacted by pelting the projection screen with beer bottles and eventually pulling down the screen.

Technological developments of VJing

An artist retreat in Owego New York called Experimental Television Center, founded in 1971, made contributions to the development of many artists by gathering the experimental hardware created by video art pioneers: Nam June Paik (vid. 1 below), Steve Rutt and Bill Etra, and made the equipment available to artists in an inviting setting for free experimentation.

Many of the outcomes debuted at the nightclub Hurrah which quickly became a new alternative for video artists who could not get their avant garde productions aired on regular broadcast outlets. Similarly, music video development was happening in other major cities around the world, providing an alternative to mainstream television.

The Dan Sandin Image Processor, or "IP," is an analog video processor with video signals sent through processing modules that route to an output color encoder. The IP's most unique attribute is its non-commercial philosophy, emphasizing a public access to processing methods and the machines that assist in generating the images. The IP was Sandin's electronic expression for a culture that would "learn to use High-Tech machines for personal, aesthetic, religious, intuitive, comprehensive, and exploratory growth."

This educational goal was supplemented with a "distribution religion" that enabled video artists, and not-for-profit groups, to "roll-your-own" video synthesizer for only the cost of parts and the sweat and labor it took to build it. It was the "Heathkit" of video art tools, with a full building plan spelled out, including electronic schematics and mechanical assembly information (effectively a score, a manual). Tips on soldering, procuring electronic parts and Printed Circuit boards, were also included in the documentation, increasing the chances of successfully building a working version of the video synthesizer.

vid. 1 merce by merce by paik PAIK & KUBOTA

1980s Important Events

In May 1980, multi media artist / filmmaker Merrill Aldighieri was invited to screen a film at the nightclub Hurrah. At this time, music video clips did not exist in large quantity and the video installation was used to present an occasional film. To bring the role of visuals to an equal level with the DJ's music, Merrill made a large body of ambient visuals that could be combined in real time to interpret the music.

Working alongside the DJ, this collection of raw visuals was mixed in real time to create a non-stop visual interpretation of the music. Merrill became the world's first full-time VJ. MTV founders came to this club and Merrill introduced them to the term and the role of "VJ",inspiring them to have VJ hosts on their channel the following year. Merrill collaborated with many musicians at the club, notably with electronic musician Richard Bone to make the first ambient music video album titled "Emerging Video".

Thanks to a grant from the Experimental Television Center, her blend of video and 16 mm film bore the influential mark of the unique Rutt Etra and Paik synthesizers. This film was offered on VHS through "High Times Magazine" and was featured in the club programming. Her next foray into the home video audience was in collaboration with the newly formed arm of Sony, Sony HOME VIDEO, where she introduced the concept of "breaking music on video" with her series DANSPAK. With a few exceptions like the Jim Carrol Band with Lou Reed and Man Parrish, this series featured unknown bands, many of them unsigned.

The rise of electronic music (especially in house and techno genres) and DJ club culture provided more opportunities for artists to create live visuals at events. The popularity of MTV lead to greater and better production of music videos for both broadcast and VHS, and many clubs began to show music videos as part of entertainment and atmosphere.

Joe Shannahan (owner of Metro in 1989-1990) was paying artists for video content on VHS. Part of the evening they would play MTV music videos and part of the evening they would run mixes from local artists Shanahan had commissioned.

Medusa's (an all-ages bar in Chicago) incorporated visuals as part of their nightly art performances throughout the early to mid 80s (1983–85).[14] Also in Chicago during the mid-80s was Smart Bar, where Metro held "Video Metro" every Saturday night.

1990s Important Events

A number of recorded works begin to be published in the 1990s to further distribute the work of VJs, such as the Xmix compilations (beginning in 1993), Future Sound of London's "Lifeforms"(VHS, 1994), Emergency Broadcast Network's "Telecommunication Breakdown" (VHS, 1995), Coldcut and Hexstatic's "Timber" (VHS, 1997 and then later on CDRom including a copy of VJamm VJ software), the "Mego Videos" compilation of works from 1996-1998 (VHS/PAL, 1999) and Addictive TV's 1998 television series "Transambient" for the UK's Channel 4 (and DVD release).

In the United States, the emergence of the rave scene is perhaps to be credited for the shift of the VJ scene from nightclubs into underground parties. From around 1991 until 1994, Mark Zero would do film loops at Chicago raves and house parties. One of the earliest large-scale Chicago raves was "Massive New Years Eve Revolution" in 1993, produced by Milwaukee's Drop Bass Network. It was a notable event as it featured the Optique Vid Tek (OVT) VJs on the bill.

This event was followed by Psychosis, held on 3 April 1993, and headlined by Psychic TV, with visuals by OVT Visuals. In San Francisco Dimension 7 were a VJ collective working the early West Coast rave scene beginning in 1993. Between 1996 and 1998, Dimension 7 took projectors and lasers to the Burningman festival, creating immersive video installations on the Black Rock desert. In the UK groups such as The Light Surgeons and Eikon were transforming clubs and rave events by combining the old techniques of liquid lightshows with layers of slide, film and video projections.

In Bristol, Children of Technology emerged, pioneering interactive immersive environments stemming from co-founder Mike Godfrey's architectural thesis whilst at university during the 1980s. Children of Technology integrated their homegrown CGI animation and video texture library with output from the interactive Virtual Light Machine (VLM), the brainchild of Jeff Minter and Dave Japp, with output onto over 500 sq m of layered screens using high power video and laser projection within a dedicated lightshow. Their "Ambient Theatre Lightshow" first emerged at Glastonbury 93 and they also provided VJ visuals for the Shamen, who had just released their no 1. hit "Ebeneezer Good" at the festival.

Invited musicians jammed in the Ambient Theatre Lightshow, using the VLM, within a prototype immersive environment. Children of Technology took interactive video concepts into a wide range of projects including show production for "Obsession" raves between 1993 and 1995, theatre, clubs, advertising, major stage shows and TV events. This included pioneering projects with 3D video / sound recording and performance, and major architectural projects in the late 1990s, where many media technology ideas were now taking hold.

Another collective, "Hex" were working across a wide range of media - from computer games to art exhibitions - the group pioneered many new media hybrids, including live audiovisual jamming, computer-generated audio performances, and interactive collaborative instruments. This was the start of a trend which continues today with many VJs working beyond the club and dance party scene in areas such as installation art. The Japanese book "VJ2000" (Daizaburo Harada, 1999) marked one of the earliest publications dedicated to discussing the practices of VJs.

Later Technological developments of VJing

The combination of the emerging rave scene, along with slightly more affordable video technology for home-entertainment systems, brought consumer products to become more widely used in artistic production. However, costs for these new types of video equipment were still high enough to be prohibitive for many artists.

There are three main factors that lead to the proliferation of the VJ scene in the 2000s:

-affordable and faster laptops;

-drop in prices of video projectors (especially after the dot-com bust where companies were loading off their goods on craigslist)

- the emergence of strong rave scenes and the growth of club culture internationally

As a result of these, the VJ scene saw an explosion of new artists and styles. These conditions also facilitated a sudden emergence of a less visible (but nonetheless strong) movement of artists who were creating algorithmic, generative visuals. The Videonics MX-1 video mixer This decade saw video technology shift from being strictly for professional film and television studios to being accessible for the prosumer market (e.g. the wedding industry, church presentations, low-budget films, and community television productions).

These mixers were quickly adopted by VJs as the core component of their performance setups. This is similar to the release of the Technics 1200 turntables, which were marketed towards homeowners desiring a more advanced home entertainment system, but were then appropriated by musicians and music enthusiasts for experimentation.

Initially, video mixers were used to mix pre-prepared video material from VHS players and live camera sources, and later to add the new computer software outputs into their mix. The 90s saw the development of a number of digital video mixers such as Panasonic's WJ-MX50, WJ-MX12, and the Videonics MX-1. Early desktop editing systems such as the NewTek Video Toaster for the Amiga computer were quickly put to use by VJs seeking to create visuals for the emerging rave scene, whilst software developers began to develop systems specifically designed for live visuals such as O'Wonder's "Bitbopper".

The first known software for VJs was Vujak - created in 1992 and written for the Mac by artist Brian Kane for use by the video art group he was part of - Emergency Broadcast Network, though it was not used in live performances. EBN used the EBN VideoSampler v2.3, developed by Mark Marinello and Greg Deocampo. In the UK, Bristol's Children of Technology developed a dedicated immersive video lightshow using the Virtual Light Machine (VLM) called AVLS or Audio-Visual-Live-System during 1992 and 1993. The VLM was a custom built PC by video engineer Dave Japp using super-rare transputer chips and modified motherboards, programmed by Jeff Minter (Llamasoft & Virtual Light Co.).

The VLM developed after Jeff's earlier Llamasoft Light Synthesiser programme. With VLM, DI's from live musicians or DJ's activated Jeff's algorithmic real-time video patterns, and this was real-time mixed using pansonic video mixers with CGI animation/VHS custom texture library and live camera video feedback. Children of Technology developed their own "Video Light" system, using hi-power and low-power video projection to generate real-time 3D beam effects, simultaneous with enormous surface and mapped projection.

The VLM was used by the Shamen, The Orb, Primal Scream, Obsession, Peter Gabriel, Prince and many others between 1993 and 1996. A software version of the VLM was integrated into Atari's Jaguar console, in response to growing VJ interest. In the mid-90s, Audio reactive pure synthesis (as opposed to clip-based) software such as Cthugha and Bomb were influential. By the late 90s there were several PC based VJing softwares available, including generative visuals programs such as MooNSTER, Aestesis, and Advanced Visualization Studio, as well as video clip players such as FLxER, created by Gianluca Del Gobbo, and VJamm.

Programming environments such as Max/MSP, Macromedia Director and later Quartz Composer started to become used by themselves and also to create VJing programs like VDMX or pixmix. These new software products and the dramatic increases in computer processing power over the decade meant that VJs were now regularly taking computers to gigs.

********************************

Motion graphics

Motion graphics are pieces of animation or digital footage which create the illusion of motion or rotation, and are usually combined with audio for use in multimedia projects. Motion graphics are usually displayed via electronic media technology, but may also be displayed via manual powered technology (e.g. thaumatrope, phenakistoscope, stroboscope, zoetrope, praxinoscope, flip book). The term distinguishes still graphics from those with a transforming appearance over time, without over-specifying the form. While any form of experimental or abstract animation can be called motion graphics, the term typically more explicitly refers to the commercial application of animation and effects to video, film, TV, and interactive applications.

********************************

Sound Art

Sound art is an artistic discipline in which sound is utilised as a primary medium. Like many genres of contemporary art, sound art may be interdisciplinary in nature, or be used in hybrid forms. Sound art can be considered as being an element of many areas such as acoustics, psychoacoustics, electronics, noise music, audio media, found or environmental sound, soundscapes, explorations of the human body, sculpture, architecture, film or video and other aspects of the current discourse of contemporary art.

In Western art, early examples include Luigi Russolo's Intonarumori or noise intoners (1913), and subsequent experiments by Dadaists, Surrealists, the Situationist International, and in Fluxus happenings. Because of the diversity of sound art, there is often debate about whether sound art falls within the domains of visual art or experimental music, or both.

Other artistic lineages from which sound art emerges are conceptual art, minimalism, site-specific art, sound poetry, electro-acoustic music, spoken word, avant-garde poetry, and experimental theatre (performance in a way wether in video or experienced by a live audience).

Origins of Sound Art

The earliest documented use of the term in the U.S. is from a catalogue for a show called "Sound/Art" at The Sculpture Center in New York City, created by William Hellermann in 1983. The show was sponsored by "The SoundArt Foundation," which Hellerman founded in 1982.

The artists featured in the show were: Vito Acconci, Connie Beckley, Bill and Mary Buchen, Nicolas Collins, Sari Dienes and Pauline Oliveros, Richard Dunlap, Terry Fox, William Hellermann, Jim Hobart, Richard Lerman, Les Levine, Joe Lewis, Tom Marioni, Jim Pomeroy, Alan Scarritt, Carolee Schneeman, Bonnie Sherk, Keith Sonnier, Norman Tuck, Hannah Wilke, Yom Gagatzi.

The following is an excerpt from the catalogue essay by art historian Don Goddard:

"It may be that sound art adheres to curator Hellermann's perception that "hearing is another form of seeing,' that sound has meaning only when its connection with an image is understood... The conjunction of sound and image insists on the engagement of the viewer, forcing participation in real space and concrete, responsive thought rather than illusionary space and thought." Sound art always takes place in an acoustic context, which may influence interpretation as much as if not more than any associated imagery. Installations of sound art rely on the acoustics of the spaces and reproduction technologies employed as can be exemplified by current practitioners such as Chris Watson.

Sound Art in Belgium

The Klankenbos (Sound forest-www.klankenbos.be) of Provinciaal Domein Dommelhof is the biggest sound art collection in public space in Europe. In the forest there are 15 sound installation pieces by artists such as Pierre Berthet, Paul Panhuysen, Geert Jan Hobbijn (Staalplaat Soundsystem), Hans van Koolwijk, and others. Yearly in Kortrijk there is the sound art festival Wilde Westen (formerly known as Happy New Ears).

In Brussels there are QO2 and Overtoon, two organisations that run artist-in-residence programs and organize events. Logos Foundation from Ghent is a sound art org run by Godfried-Willem Raes.

Croatia

In Zadar there is the Sea Organ which plays music by way of sea waves and tubes located underneath a set of large marble steps. Germany Originally from Amsterdam, but moved to Berlin is Staalplaat, a record label focused on sound art and experimental music. Transmediale is a yearly festival focused on media art, covering many sound art performances and installations.

The Netherlands

The Dutch sound art tradition started more or less in the Philips Natuurkundig Laboratorium where Dick Raaijmakers worked in the 60s. Paul Panhuysen and Remko Scha developed many early sound art pieces in the 70s and 80s and set up the Apollohuis in Eindhoven. STEIM. WORM, Extrapool are active organisations that have sound art activities. Polderlicht was a sound art festival running from 2000–2015. Instrument Inventors Initiative (iii) is a The Hague based organisation focused on the creation of sound art pieces. The organisation has an active artist-in-residence program and continuously invites sound artists to make new works at their location. The Netherlands have three academies where you can study in the direction of sound art Institute of Sonology, Art Science at Royal Academy of Art, The Hague and at the Utrecht School of the Arts in Utrecht.

Norway

Lydgalleriet (The Soundgallery) is a non-commercial gallery for sound based art practices, situated in the centre of Bergen. Sweden Playing the Building was an art installation by David Byrne, ex singer of Talking Heads, and Färgfabriken, an independent art venue in Stockholm. Elektronmusikstudion is an active organisation.

United Kingdom

A known sound art pieces in the UK are Blackpool High Tide Organ and Singing Ringing Tree. Although not build as sound art pieces, the UK has several acoustic mirrors along the coastline often explored by field recorders. (vid.2 below)

vid.2 - Testing The Sound Mirrors That Protected Britain

Sound sculpture (related to sound art and sound installation) is an intermedia and time based art form in which sculpture or any kind of art object produces sound, or the reverse (in the sense that sound is manipulated in such a way as to create a sculptural as opposed to temporal form or mass).

Most often sound sculpture artists were primarily either visual artists or composers, not having started out directly making sound sculpture. Cymatics and kinetic art have influenced sound sculpture. Sound sculpture is sometimes site-specific. Grayson described sound sculpture in 1975 as "the integration of visual form and beauty with magical, musical sounds through participatory experience."

Sound installation

Sound installation (related to sound art and sound sculpture) is an intermedia and time based art form. It is an expansion of an art installation in the sense that it includes the sound element and therefore the time element.

The main difference with a sound sculpture is that a sound installation has a three-dimensional space and the axes with which the different sound objects are being organized are not exclusively internal to the work, but also external.

A work of art is an installation only if it makes a dialog with the surrounding space. A sound installation is usually a site-specific but sometimes it can be readapted to other spaces. It can be made either in close or open spaces, and context is fundamental to determine how a sound installation will be aesthetically perceived.

The difference between a regular art installation and a sound installation is that the later one has the time element, which gives the visiting public the possibility to stay a longer time due possible curiosity over the development of sound. This temporal factor also gives the audience the excuse to explore the space thoroughly due to the dispositions of the different sounds in space.

Sound installations sometimes use interactive art technology (computers, sensors, mechanical and kinetic devices, etc.) but we also find this type of art form using only sound sources placed in different space points (like speakers), or acoustic music instruments materials like piano strings that are played by a performer or by the public (see Paul Panhuysen).

Music visualization

Music visualization or music visualisation, a feature found in electronic music visualizers and media player software, generates animated imagery based on a piece of music. The imagery is usually generated and rendered in real time and in a way synchronized with the music as it is played.

Visualization techniques range from simple ones (e.g., a simulation of an oscilloscope display) to elaborate ones, which often include a number of composited effects. The changes in the music's loudness and frequency spectrum are among the properties used as input to the visualization.

Effective music visualization aims to attain a high degree of visual correlation between a musical track's spectral characteristics such as frequency and amplitude and the objects or components of the visual image being rendered and displayed. (Important!)

Audiovisual Art

Audiovisual art is the exploration of kinetic abstract art and music or sound set in relation to each other. It includes visual music, abstract film, audiovisual performances and installations.

The book Art and the Senses cites the Italian Futurist artists, Fortunato Depero and Luigi Russolo as designing art machines in 1915 to create a multisensory experience of sound, movement and colour.

In the 1970s Harry Bertoia created sound sculptures of objects to have a multisensory effect, exploring the relationships between the sound, the initiating event and the material properties of the objects.

In an example with overt musical connections, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics cites musician Brian Williams (aka Lustmord) as someone whose practise crosses audiovisual art and mainstream media, where his work is "not traditionally 'musical'" and has "clearly visual aspects".

Non-narrative Film

Non-narrative film is an aesthetic of (cinematic) film that does not narrate, or relate "an event, whether real or imaginary". It is usually a form of art film or experimental film, not made for mass entertainment. Narrative film is the dominant aesthetic, though non-narrative film is not fully distinct from that aesthetic. While the non-narrative film avoids "certain traits" of the narrative film, it "still retains a number of narrative characteristics".

Narrative film also occasionally uses "visual materials that are not representational". Although many abstract films are clearly devoid of narrative elements, distinction between a narrative film and a non-narrative film can be rather vague and is often open for interpretation.

Unconventional imagery, concepts and structuring can obscure the narrativity of a film. Terms like "absolute film", "cinéma pur", "true cinema" and "integral cinema" have been used for non-narrative films that aimed to create a purer experience of the distinctive qualities of film, like movement, rhythm and changing visual compositions. More narrowly, "absolute film" was used for the works of a group of filmmakers in Germany in the 1920s, that consisted, at least initially, of animated films that were totally abstract.

The French term "cinéma pur" was coined to describe the style of several filmmakers in France in the 1920s, whose work was non-narrative, but hardly ever non-figurative. Much of surrealist cinema can be regarded as non-narrative films and partly overlaps with the dadaist cinéma pur movement.

Musical Influence in Non-narrative Film

Music was an extremely influential aspect of absolute film, and one of the biggest elements, other than art, used by abstract film directors. Absolute film directors are known to use musical elements such as rhythm/tempo, dynamics, and fluidity.

These directors sought to use this to add a sense of motion and harmony to the images in their films that was new to cinema, and was intended to leave audiences in awe. In her article "Visual Music" Maura McDonnell compared these film's to musical compositions due to their careful articulation of timing and dynamics.

The history of abstract film often overlaps with the concerns and history of visual music. Some films are very similar to electronic music visualization, especially when electronic devices (for instance oscilloscopes) were used to generate a type of motion graphics in relation to music, except that the images in these films are not generated in real-time.

Abstract film Abstract film or absolute film is a subgenre of experimental film and a form of abstract art. Abstract films are non-narrative, contain no acting and do not attempt to reference reality or concrete subjects. They rely on the unique qualities of motion, rhythm, light and composition inherent in the technical medium of cinema to create emotional experiences.

Many abstract films have been made with animation techniques. The distinction between animation and other techniques can be rather unclear in some films, for instance when abstract objects were filmed in motion or with camera movement when very similar results could have been obtained with stop motion techniques.

Non-narrative Film in the 1920s :The Absolute Film Movement

Some of the earliest abstract motion pictures known to survive are those produced by a group of artists working in Germany in the early 1920s: Walter Ruttmann, Hans Richter, Viking Eggeling and Oskar Fischinger.

Absolute film pioneers sought to create short length and breathtaking films with different approaches to abstraction-in-motion: as an analogue to music, or as the creation of an absolute language of form, a desire common to early abstract art.

Ruttmann wrote of his film work as "painting in time". Absolute filmmakers used rudimentary handicraft, techniques, and language in their short motion pictures that refuted the reproduction of the natural world, instead, focusing on light and form in the dimension of time, impossible to represent in static visual arts.

Viking Eggeling came from a family of musicians and analysed the elements of painting by reducing it into his "Generalbass der Malerei", a catalogue of typological elements, from which he would create new "orchestrations". In 1918 Viking Eggeling had been engaging in Dada activities in Zürich and befriended Hans Richter.

According to Richter, absolute film originated in the scroll sketches that Viking Eggeling made in 1917–1918. On paper rolls up to 15 meters long, Eggeling would draw sketches of variations of small graphic designs, in such a way that a viewer could follow the changes in the designs when looking at the scroll from beginning to end.

For a few years Eggeling and Richter worked together, each on their own projects based on these ides, and created thousands of rhythmic series of simple shapes. In 1920 they started working on film versions of their work.

Walter Ruttmann, trained as a musician and painter, gave up painting to devote himself to film. He made his earliest films by painting frames on glass in combination with cutouts and elaborate tinting and hand-coloring.

His Lichtspiel: Opus I was first screened in March 1921 in Frankfurt. Hans Richter finished his first film Rhythmus 21 (a.k.a. Film ist Rhythmus) in 1921, but kept changing elements until he first presented the work on 7 July 1923 in Paris at the dadaist Soirée du coeur à barbe program in Théâtre Michel. It was an abstract animation of rectangular shapes, partly inspired by his connections with De Stijl.

Founder Theo van Doesberg had visited Richter and Eggeling in December 1920 and reported on their film works in his magazine De Stijl in May and July 1921. Rhytmus 23 and the colourful Rhythmus 25 followed similar principles, with noticeable suprematist influence of Kasimir Malevich's work. Rhythmus 25 is considered lost. Eggeling debuted his Horizontal-vertikalorchester in 1923. The film is now considered lost. In November 1924 Eggeling was able to present his new finished film Symphonie diagonale in a private screening. On 3 May 1925 the Sunday matinee program Der absolute Film took place in the UFA-Palast theater at the Kurfurstendamm in Berlin. Its 900 seats soon sold out and the program was repeated a week later.

Eggeling's Symphonie diagonale, Richter's Rhythmus 21 and Rhythmus 23, Walter Ruttmann's Opus II, Opus III and Opus IV were all shown publicly for the first time in Germany, along with the two French dadaist "cinéma pur" films Ballet Mécanique and René Clair's Entr'acte, and Ludwig Hirschfeld-Mack's performance with a type of color organ. Eggeling happened to die a few days later. Oskar Fischinger met Walter Ruttmann at rehearsals for screenings of Opus I with live music in Frankfurt. In 1921 he started experimenting with abstract animation in wax and clay and with colored liquids. He used such early material in 1926 in multiple-projection performances for Alexander Laszlo's Colorlightmusic concerts. That same year he released his first abstract animations and would continue with a few dozens of short films over the years. The Nazis censorship against so-called "degenerate art" prevented the German abstract animation movement from developing after 1933.

Non-narrative Film in the 1930s - 1960s: The Absolute Film Movement

Mary Ellen Bute started making experimental films in 1933, mostly with abstract images visualizing music. Occasionally she applied animation techniques in her films. Len Lye made the first publicly released direct animation entitled A Colour Box in 1935.

The colorful production was commissioned to promote the General Post Office. Oskar Fischinger moved to Hollywood in 1936 when he had a lucrative agreement to work for Paramount Pictures. A first film, eventually entitled Allegretto, was planned for inclusion in the musical comedy The Big Broadcast of 1937.

Paramount had failed to communicate that it would be in black and white, so Fischinger left when the studio refused to even consider a color test of the animated section. He then created An Optical Poem (1937) for MGM, but received no profits because of the way the studio's bookkeeping system worked. Walt Disney had seen Lye's A Colour Box and became interested in producing abstract animation. A first result was the Toccata and Fugue in D Minor section in the "concert film" Fantasia (1940). He hired Oskar Fischinger to collaborate with effects animator Cy Young, but rejected and altered much of their designs, causing Fischinger to leave without credit before the piece was completed.

Fishinger's two commissions from The Museum of Non-Objective Painting did not really allow him the creative freedom that he desired. Frustrated with all the trouble with filmmaking he experienced in America, Fischinger did not make many films afterwards. Apart from some commercials, the only exception was Motion Painting No. 1 (1947), which won the Grand Prix at the Brussels International Experimental Film Competition in 1949. Norman McLaren, having carefully studied Lye's A Colour Box, founded the National Film Board of Canada's animation unit in 1941.

Direct animation was seen as a way to deviate from cel animation and thus a way to stand out from the many American productions. McLaren's direct animations for NFB include Boogie-Doodle (1941), Hen Hop (1942), Begone Dull Care (1949) and Blinkity Blank (1955). Harry Everett Smith created several direct films, initially by hand-painting abstract animations on celluloid. His Early Abstractions was compiled around 1964 and contains early works that may have been created since 1939, 1941 or 1946 until 1952, 1956 or 1957. Smith was not very concerned about keeping documentation about his oeuvre and frequently re-edited his works.

Cinéma Pur

Cinéma pur (French for "Pure Cinema") was an avant-garde film movement of French filmmakers, who "wanted to return the medium to its elemental origins" of "vision and movement." It declares cinema to be its own independent art form that should not borrow from literature or stage. As such, "pure cinema" is made up of nonstory, noncharacter films that convey abstract emotional experiences through unique cinematic devices such as camera movement and camera angles, close-ups, dolly shots, lens distortions, sound-visual relationships, split-screen imagery, super-impositions, time-lapse photography, slow motion, trick shots, stop-action, montage (the Kuleshov Effect, flexible montage of time and space), rhythm through exact repetition or dynamic cutting and visual composition.

Cinéma pur started around the same period with the same goals as the absolute film movement and both mainly concerned dadaists. Although the terms have been used interchangeably, or to differentiate between the German and the French filmmakers, a very noticeable difference is that very few of the French cinéma pur films were totally non-figurative or contained traditional (drawn) animation, instead mainly using radical types of cinematography, special effects, editing, visual effects and occasionally some stop motion.

History of Cinema Pur

History The term was coined by filmmaker Henri Chomette, brother of filmmaker René Clair. Photographer and filmmaker Man Ray (pictured here in 1934) was part of the Dadaist "cinema pur" film movement, which influenced the development of art film.

The cinéma pur film movement included Dada artists, such as Man Ray, René Clair and Marcel Duchamp. The Dadaists saw in cinema an opportunity to transcend "story", to ridicule "character," "setting," and "plot" as bourgeois conventions, to slaughter causality by using the innate dynamism of the motion picture film medium to overturn conventional Aristotelian notions of time and space.

Man Ray's Le Retour à la Raison (2 mins) premiered in July 1923 at the 'Soirée du coeur à barbe" program in Paris. The film consisted mainly of abstract textures, with moving photograms that were created directly on the film strip, abstract forms filmed in motion, and light and shadow on the nude torso of Kiki of Montparnasse (Alice Prin). Man Ray later made Emak-Bakia (16 mins, 1926); L'Étoile de Mer (15 mins, 1928); and Les Mystères du Château de Dé (27 mins, 1929). Dudley Murphy had seen Man Ray's Le Retour à la Raison and proposed to collaborate on a longer film.

They shot all kinds of material in the street and in a studio, used Murphy's special beveled lenses and crudely animated showroom dummy legs. They chose the title Ballet Mécanique from an image by Francis Picabia that had been published in his New York 391 magazine, which had also featured a poem and art by Man Ray. They ran out of money before they could complete the film. Fernand Léger helped financing the completion and contributed a cubist Charlie Chaplin image that was jerkily animated for the film. It is unclear if Léger contributed anything else, but he got to distribute the film in Europe and took sole credit for the film. Ray had backed out of the project before completion and did not want his name to be used. Murphy had gone back tot the U.S.A. shortly after editing the final version, with the deal that he could distribute the film there.

Avant-garde artist Francis Picabia and composer Erik Satie asked René Clair to make a short film to be shown as the entr'acte of their Dadaist ballet Relâche for Ballets suédois. The result became known as Entr'acte (1924) and featured cameo appearances by Francis Picabia, Erik Satie, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, composer Georges Auric, Jean Borlin (director of the Ballets Suédois) and Clair himself. The film showed absurd scenes and used slow motion and reverse playback, superimpositions, radical camera angles, stop motion and other effects.

Erik Satie composed a score that was to be performed in sync with certain scenes. Henri Chomette adjusted the film speed and shot from different angles to capture abstract patterns in his 1925 film Jeux des reflets de la vitesse (The Play of Reflections and Speed). His 1926 film Cinq minutes du cinéma pur (Five minutes of Pure Cinema) reflected a more minimal, formal style.

The movement also encompasses the work of the feminist critic/cinematic filmmaker Germaine Dulac, particularly Thème et variations (1928), Disque 957 (1928), and Cinegraphic Study of an Arabesque. In these, as well as in her theoretical writing, Dulac's goal was "pure" cinema, free from any influence from literature, the stage, or even the other visual arts. The style of the French cinéma pur artists probably had a strong influence on newer works by Ruttmann and Richter, which would no longer be totally abstract.

Richter's Vormittagsspuk (Ghosts before Breakfast) (1928) features some stop motion, but mostly shows live action material with cinematographic effects and visual tricks. It is usually regarded as a dadaist film.

Intermedia

Intermedia was a term used in the mid-1960s by Fluxus artist Dick Higgins to describe various inter-disciplinary art activities that occurred between genres in the 1960s.

The areas such as those between drawing and poetry, or between painting and theatre could be described as "intermedia". With repeated occurrences, these new genres between genres could develop their own names (e.g. visual poetry, performance art); historically, an example is haiga, which combined brush painting and haiku into one composition.

Higgins described the tendency of what he thought was the most interesting and best in the new art to cross boundaries of recognized media or even to fuse the boundaries of art with media that had not previously been considered for art forms, including computers.

Part of the reason that Duchamp's objects are fascinating while Picasso's voice is fading is that the Duchamp pieces are truly between media, between sculpture and something else, while a Picasso is readily classifiable as a painted ornament. Similarly, by invading the land between collage and photography, the German John Heartfield produced what are probably the greatest graphics of our century ... — Higgins, Intermedia, 1965, Leonardo, vol. 34, p. 49

With characteristic modesty, he often noted that Samuel Taylor Coleridge had first used the term. Gene Youngblood also described intermedia, beginning in his "Intermedia" column for the Los Angeles Free Press beginning in 1967 as a part of a global network of multiple media that was "expanding consciousness"—the intermedia network—that would turn all people into artists by proxy. He gathered and expanded ideas from this series of columns in his 1970 book Expanded Cinema, with an introduction by Buckminster Fuller.

In 1968, Hans Breder founded the first university program in the United States to offer an M.F.A. in intermedia. The Intermedia Area at The University of Iowa graduated artists such as Ana Mendieta and Charles Ray. In addition, the program developed a substantial visiting artist tradition, bringing artists such as Dick Higgins, Vito Acconci, Allan Kaprow, Karen Finley, Robert Wilson and others to work directly with Intermedia students.

Over the years, especially on the Iowa campus, intermedia has been used interchangeably with multi-media. However, recently the latter term has become identified with electronic media in pop-culture.

While Intermedia values both disciplines, the term "Intermedia" has become the preferred term for interdisciplinary practice. Two other prominent University programs that focus on intermedia are the Intermedia program at Arizona State University and the Intermedia M.F.A. at the University of Maine, founded and directed by Fluxus scholar and author Owen Smith.

Ideophones

Ideophones are words that evoke an idea in sound, often a vivid impression of certain sensations or sensory perceptions, e.g. sound (onomatopoeia), movement, color, shape, or action.

Ideophones are found in many of the world's languages, though they are claimed to be relatively uncommon in Western languages. In many languages, they are a major lexical class of the same order of magnitude as nouns and verbs: dictionaries of languages like Japanese, Korean, and Zulu list thousands of them.

The word class of ideophones is sometimes called phonosemantic to indicate that it is not a grammatical word class in the traditional sense of the word (like 'verb' or 'noun'), but rather a lexical class based on the special relation between form and meaning exhibited by ideophones.

In the discipline of linguistics, ideophones have long been overlooked or treated as mysterious words, though a recent surge of interest in sound symbolism, iconicity and linguistic diversity has brought them renewed attention.

Ideophones in English

True ideophones are few in English: most ideophone-like words are either onomatopoeia like murmur or sound-symbolic ordinary words like pitter-patter, where patter is a normal word but pitter is added to give an impression of lightness and quickness.

-zigzag; an onomatopoetic impression of sharp edges or angles

-gaga; unintelligible utterances

-boing; the sound of a spring being released boom; the sound of an explosion bang; the sound of a gunshot

-swish; the sound of swift movement

-splish-splash; the sound of water splashing

-ta-daa!; the sound of a fanfare thud; the sound of something heavy falling on the ground

-tick-tock; the sound of time passing zoom; the sound of something rushing past, with doppler effect

-helter-skelter; hurriedly, recklessly

Other ideophones can appear in cartoons; in particular, the words in jagged balloons usually called sound effects are typically ideophones.

Ideophones in German

-Zickzack; a zigzag line or shape

-ratzfatz; very fast

-zack, zack!; quickly, immediately, promptly

-holterdiepolter; helter-skelter, pell-mell

-pillepalle; pish-posh, petty, irrelevant

-plemplem; crazy, gaga, cuckoo

Ideophones in Tamil

Tamil The Tamil language uses a lot of ideophones, both in spoken (colloquial) and in formal usage.

-sora sora (சொற சொற) — rough (the sound produced when rubbing back and forth on a rough surface)

-vazha-vazha (வழவழ) - smooth, slippery

-mozhu-mozhu (மொழுமொழு) - smooth (surface)

-kozhu-kozhu (கொழுகொழு) - plump

-buzu-buzu (புசுபுசு) - soft and bushy

-gidu-gidu (கிடுகிடு) - quickly, fast

-mada-mada (மடமட) - quickly, fast

-masa-masa (மசமச) - sluggish, lethargic

-viru-viru (விறுவிறு) - energetically

-choda-choda (சொதசொத) - marshy, waterlogged

-paLa-paLa (பளபள) - glittering, shiny

-veda-veda (வெடவெட) - shaking, trembling

-chuda-chuda (சுடச்சுட) - piping hot

Ideophones in Japanese

The Japanese language has thousands of ideophones, often called mimetics. The constructions are quite metrical 2-2, or 3-3, where morae play a role in the symmetry. The first consonant of the second item of the reduplication may become voiced if phonological conditions allow.

Japanese ideophones are used extensively in daily conversations as well as in the written language.

-doki doki (ドキドキ) — heartbeat: excitement

-kira kira (キラキラ) — glitter

-shiin (シーン) — silence

-niko niko (ニコニコ) — smile

-Jii (じ-) — stare

also

-jirojiro (to) [miru] じろじろ(と)[見る] [see] intently (= stare)

-kirakira (to) [hikaru] きらきら(と)[光る] [shine] sparklingly

-giragira (to) [hikaru] ぎらぎら(と)[光る] [shine] dazzlingly

-guzu guzu [suru] ぐずぐず[する] procrastinating or dawdling (suru not optional)

-shiin to [suru] しいんと[する] [be (lit. do)] quiet (suru not optional)

-pinpin [shite iru] ぴんぴん[している] [be (lit. do)] lively (shite iru not optional)

-yoboyobo ni [naru] よぼよぼに[なる] [become] wobbly-legged (from age)

Thought-Forms (book)